The Evolution and Function of the avian neck

2015-2024

Flight has been an enormously successful evolutionary innovation for birds, however it has its downsides. Many animals use their forelimbs to grasp objects and interact with their surroundings, however the wings of birds are so highly tuned for powered flight that they can't effectively be used to manipulate their environment. As always, evolution has arrived at an incredible solution: birds utilise their head and neck as a 'surrogate forelimb' in order to capture prey (including spearfishing!), clean themselves, use tools and even to climb trees.

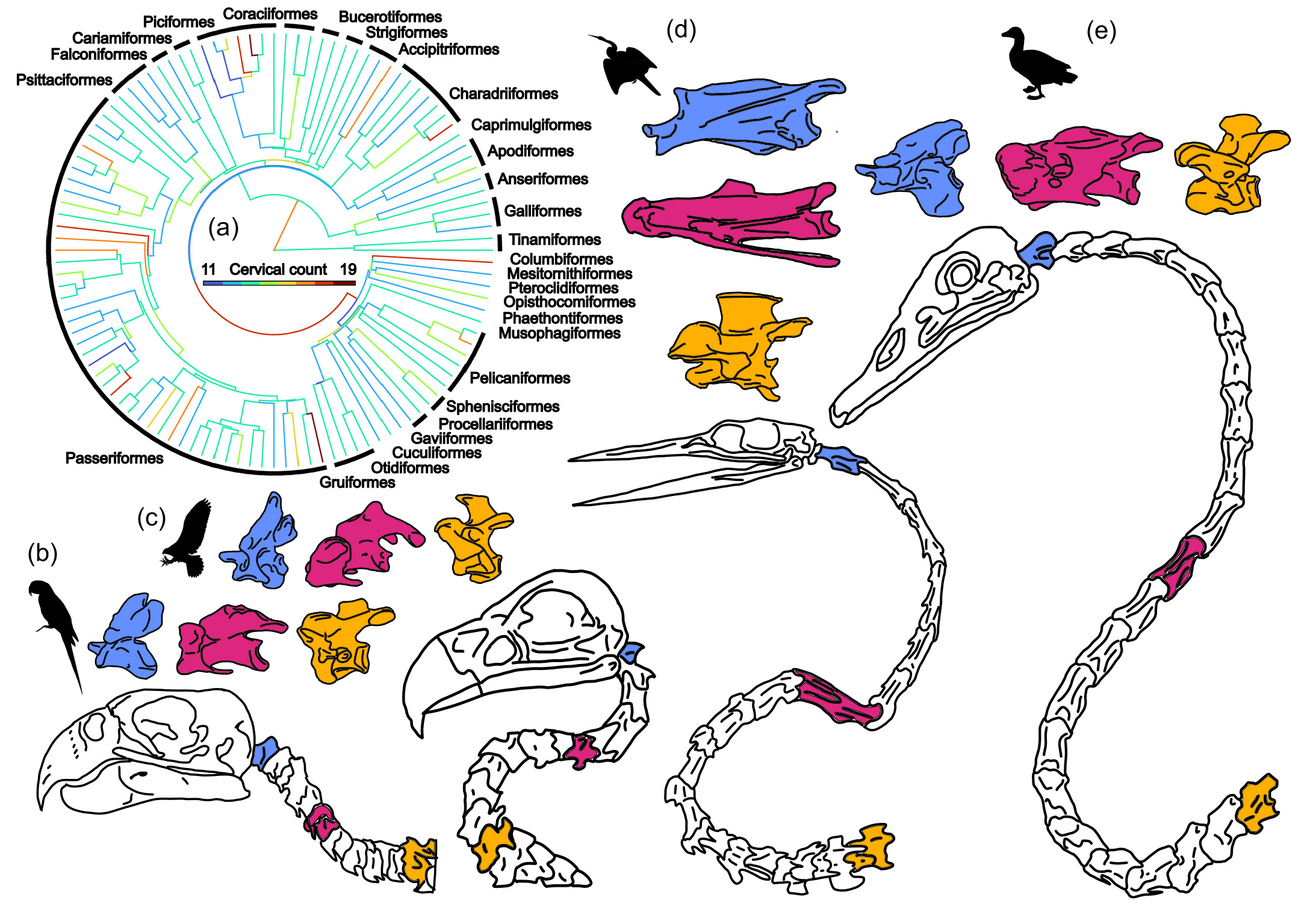

The neck of birds displays a remarkable level of morphological diversity - from the length and general shape of the whole neck, right down to specific differences of individual vertebrae (see image below) and this diversity is hypothesised to be the result of the neck becoming a 'surrogate forelimb' after the evolution of flight. However this hypothesis (up until this project) has never been formally tested. Back in 2015 I sought to answer this question as part of my PhD, but as with most academic endeavors it only spawned more questions.

Since 2015 I have used a multidisciplinary approach to document the variation in the musculoskeletal biology of bird necks in order to investigate the evolutionary and ecological forces that have shaped neck evolution within this group of animals. With the help of many fabulous collaborators I have utilised 3D geometric morphometrics, muscle dissection, phylogenetic comparative methods, CT scanning, and range of motion analysis to understand the form, function and evolution of the neck of birds in a holistic manner. This work has culminated in multiple research publications and is effectively summarised here, as well as in podcast form (edited and hosted by the excellent Palaeocast)

.

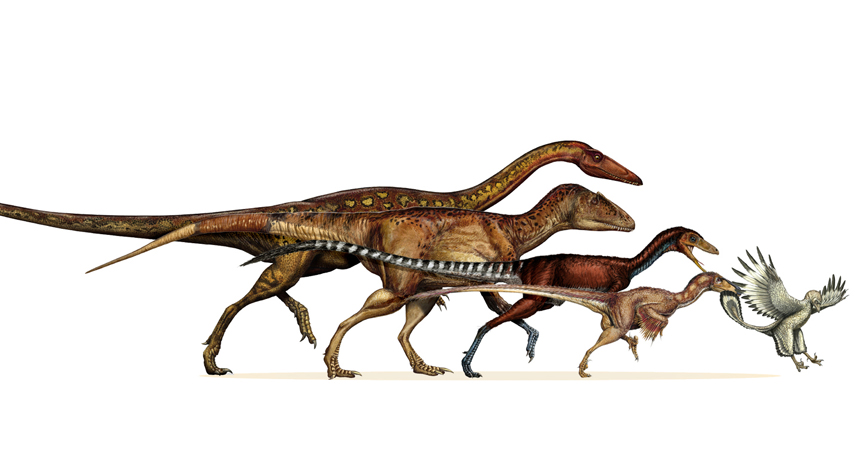

Whilst we (along with many other amazing research teams) are beginning to unravel the evolutionary story behind the diversity of neck morphologies observed in modern birds, the next phase of the project is to understand what evolutionary forces gave rise to the long and flexible neck of birds. In order to answer this question we must now look to the past and incorporate data from the ancestors of birds, the dinosaurs. The dinosaur bodyplan underwent radical changes throughout the dinosaur-bird transition such as a reduction of the massive tail and the evolution of feathers. These changes also included a reduction in head size and an expansion of the forelimb to become a wing.

We now hypothesise that with a lighter head the neck was more freely able to co-evolve with the wing, and the functional burden of environmental manipulation was shifted from the forelimbs to the head and neck. This work is currently ongoing and I am in the process of collecting dinosaur data from exciting museums around the world!